Colbert, Z. (2025). Seven Hundred Thousand Adobe Blocks: The Law of the River, Irrigation, and Incarceration at Poston. Journal of Architectural Education, 79(1), 206-227.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10464883.2025.2463299

Excerpt:

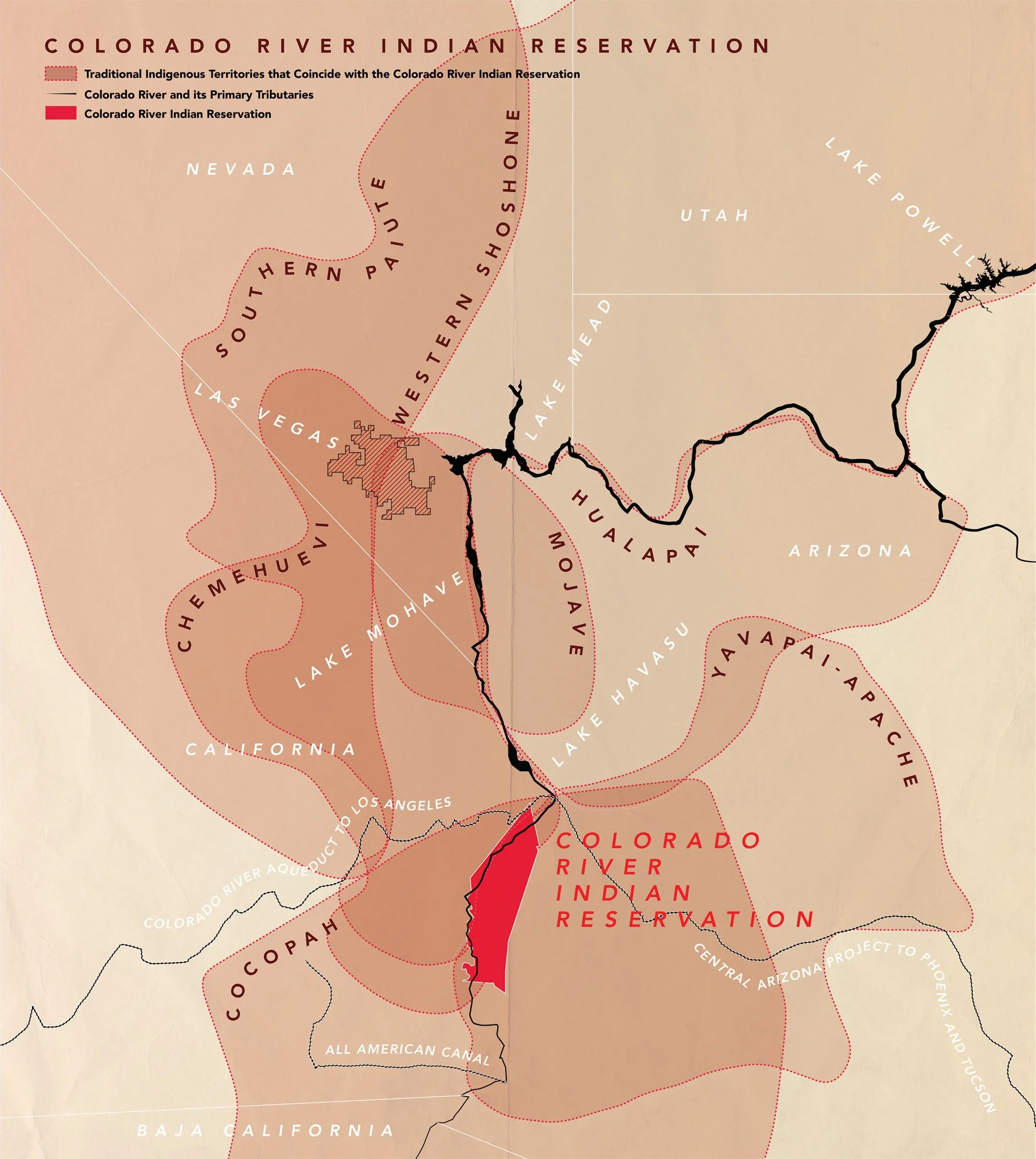

“This condition—architecture’s deep ties to extractivism, exploitative labor systems, and industrialized material manufacturing—reflects the broader context of this essay: infrastructures governed by the Law of the River perpetuate US colonial and extractive legacies through hydraulic systems that reinforce hegemonic power structures. The forces that led to the establishment of concentration camps at Poston continue to underpin spatial practices across the southwestern US today. The Law of the River shapes how people relate to the land—and through this relationship, the Law of the River also governs how they interact with each other and with the more-than-human natural world. This creates both a physical and cognitive landscape where laws, policies, infrastructures, spatial practices, and worldviews collaborate to legitimize certain social structures—such as racial and class hierarchies—and the commodification of nature, while marginalizing others. To confront and dismantle the Law of the River, better understanding the political capacity of architecture is essential. ”

The call for JAE 79:1: Architecture Beyond Extraction invited contributors to interrogate the forms of extractivism that shape architectural practice.Work that exposes extractivism’s forms of violence—while imagining alternative modes of practice grounded in care, reciprocity, and solidarity.

This issue was assembled, submitted, peer-reviewed, and editorially advanced—with publication agreements fully executed—before ACSA’s unilateral decision to halt the JAE issue on Palestine. Despite repeated appeals, ACSA refused to permit any contextual statement in this issue—and instead isolated authors and editors through opaque and inconsistent communication.

So we must ask: what does it mean to critique extractivism while suppressing scholarship on settler colonialism, imperial violence, and the contested politics of land in Palestine—the very forces that underpin extractivist regimes? How can we celebrate non-extractive practices in design—in this final issue of JAE—while ACSA silences those who speak most urgently to power?

If we are to imagine a world beyond extractivism, our scholarly platforms must embody the values they claim to uphold. Extractivism and its violences are not only material—they are also political, institutional, and epistemic. To critique extractivism meaningfully, we must confront the structures that continue to sanction ecocide and genocide.

The Enemy Aliens Act—used to forcibly incarcerate over 125,000 Japanese Americans to concentration camps like Poston—has been revived by the Trump administration to menace, incarcerate, and deport those othered and targeted without due process.

This continuity is not incidental.

The same legal scaffolding that constructed concentration camps at Poston continues to underlie US border militarization, settler sovereignty, and racialized surveillance. Then and now, architecture becomes instrumentalized for power, and for extraction: of land, labor, and life itself.

For ACSA to silence scholarship that interrogates these histories in Palestine is to ignore the very lesson that Poston teaches. That architecture embodies and mobilizes power because it is always implicated in the entwined spatial, material, and social world systems it inhabits. If academic platforms cannot hold space for these inquiries, they risk reproducing the very violence of extraction they claim to critique.